A man suffocates in a cave. Outside there is a carnival….

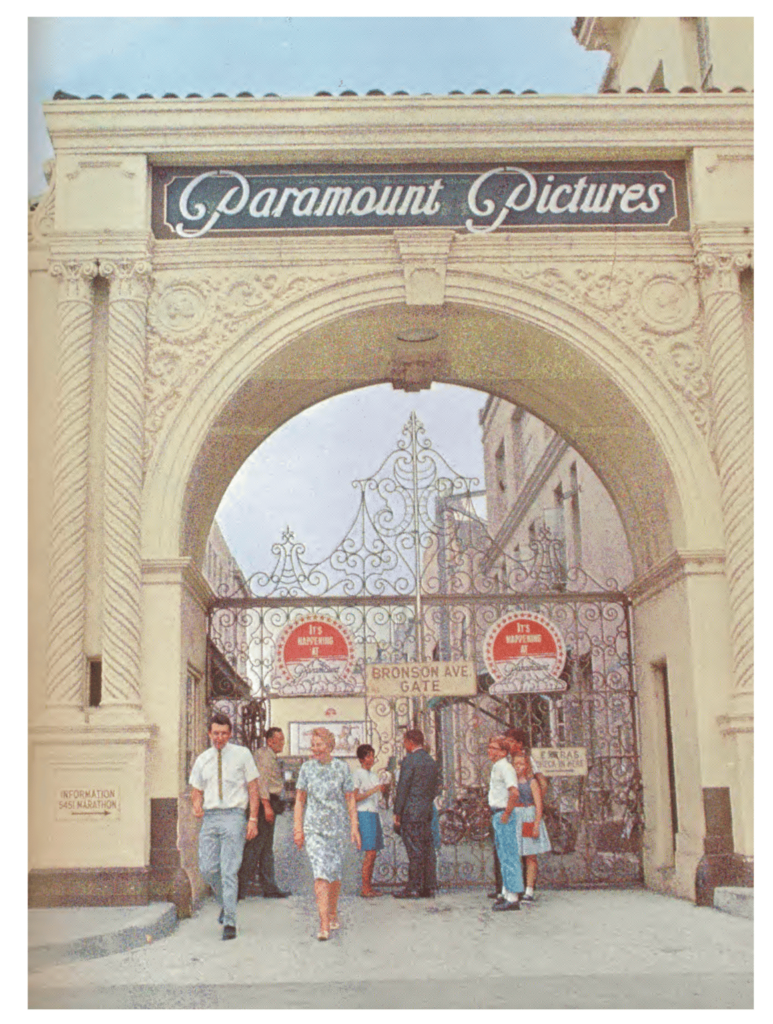

This is the premise for the 1951 Paramount Pictures film Ace in the Hole.

Stay with me here…

Still from Ace in the Hole, dir. Billy Wilder, Paramount Pictures, 1951

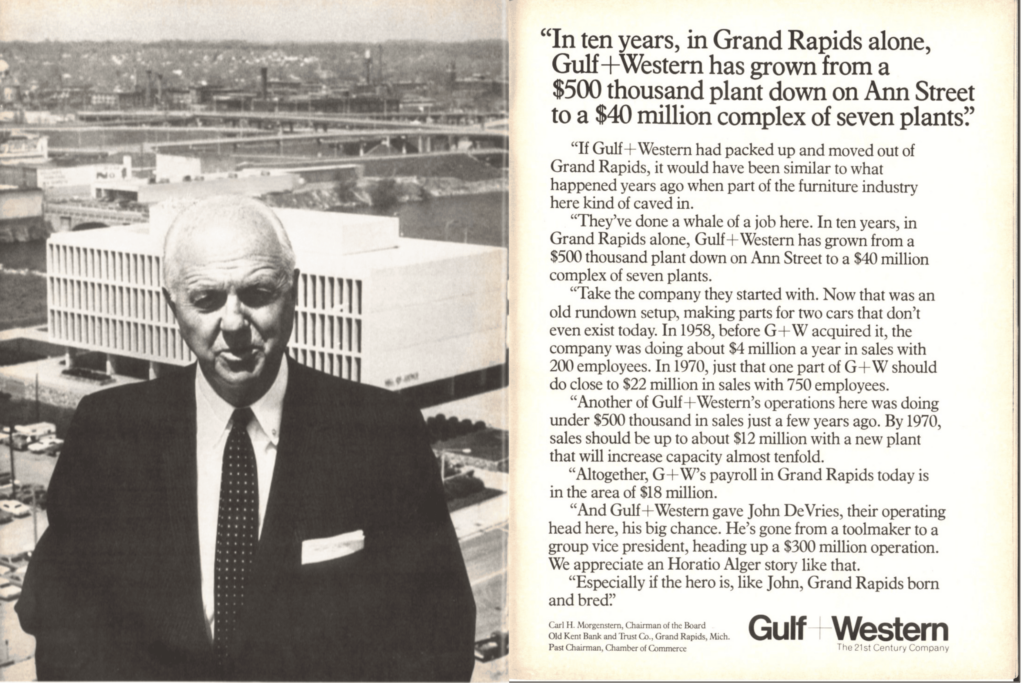

70 years ago, a company called Gulf and Western Industries was founded at the intersection of Ann and Alpine. They started as a company that made bumpers.

That site is where you saw my billboard.

Gulf and Western’s first factory at 1860 Alpine/740 Ann, c. 1964. A chrome-plated bumper comes off the line. Courtesy Grand Rapids Public Library/Grand Rapids History Center

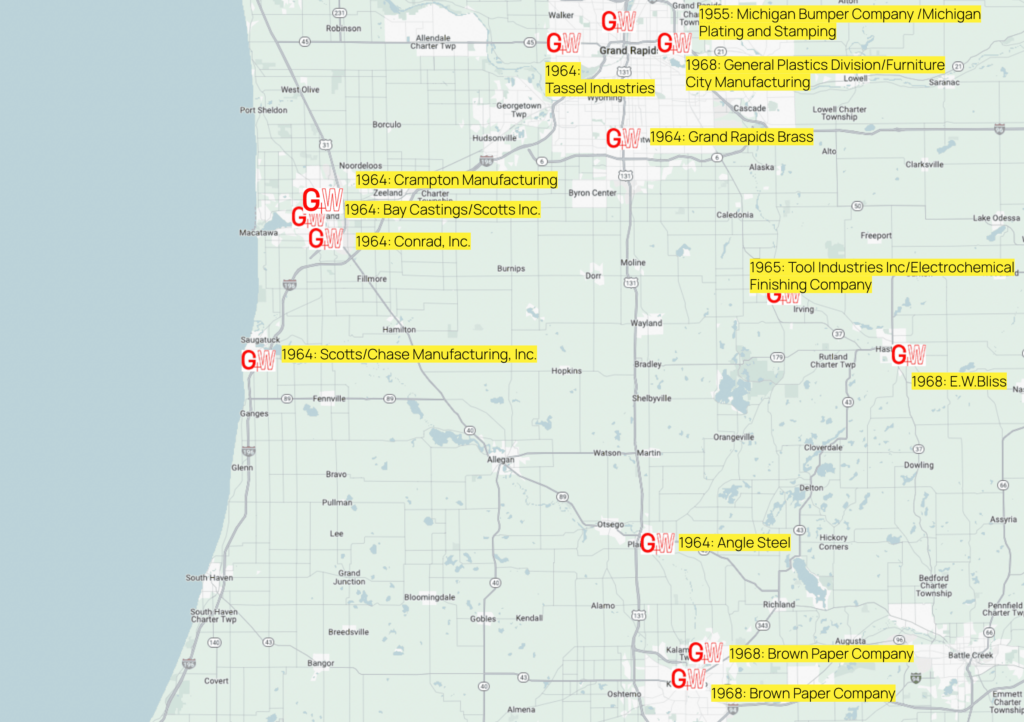

And then from that site at Ann and Alpine, over the course of a decade Gulf and Western built a kingdom of industrial sites, first in West Michigan and then all over the world. They seemed to produce almost everything. Among these goods were paper products (Brown Paper Company in Kalamazoo), brass trim for cabinets (Grand Rapids Brass), radio dials (Tassel Hardware in Standale) and decorative auto parts (Furniture City Manufacturing in Middleville).

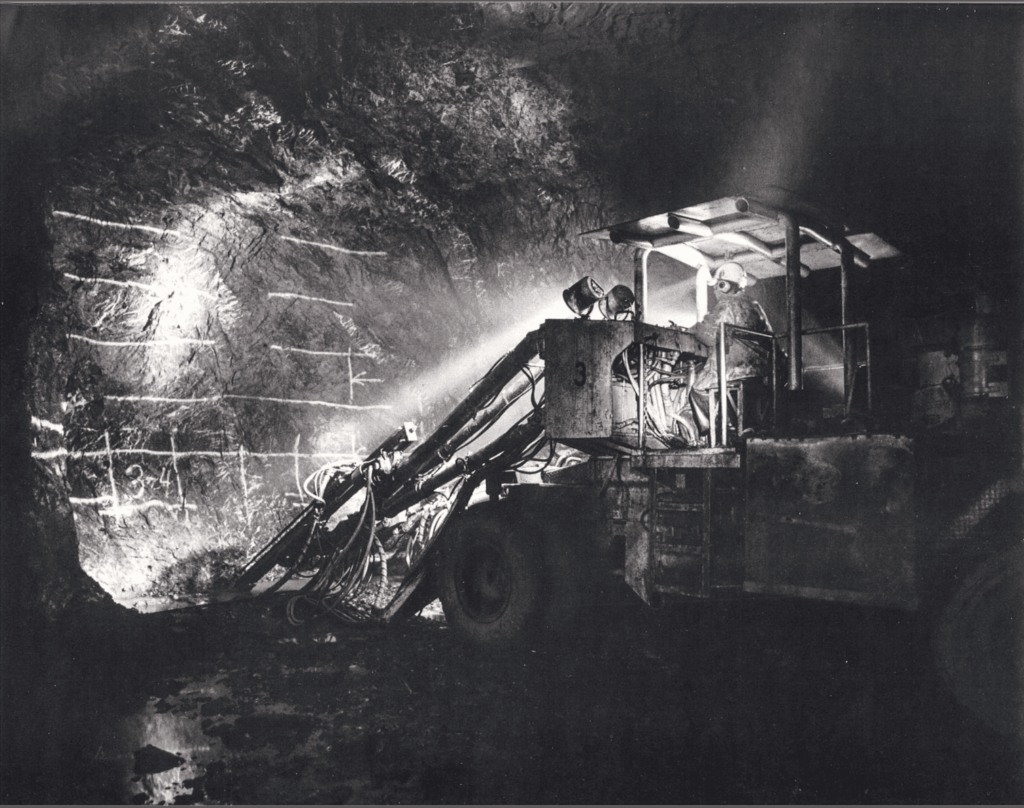

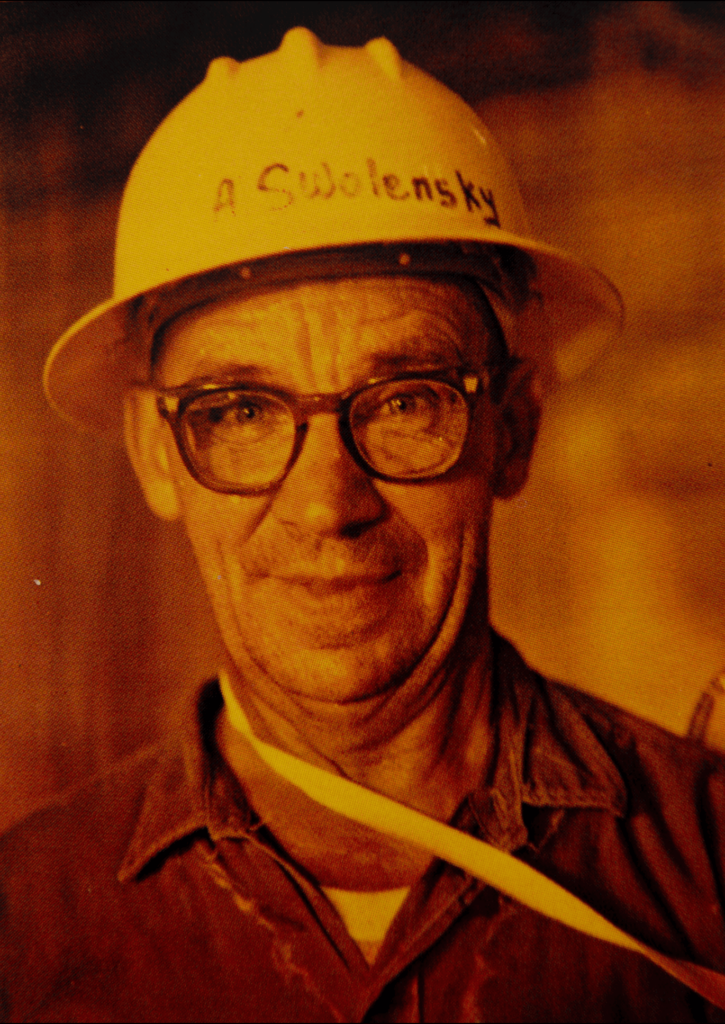

1. New Jersey Zinc operation and Consolidated Cigar factory from Gulf and Western’s newsletters to employees; 2. Worker at Brown Paper Company from Gulf and Western’s 1977 Annual Report 3. Portrait of a zinc miner from 1974 Annual Report

Gulf and Western’s factory sites in West Michigan and their opening dates.

They manufactured the presses used in factories (E.W. Bliss in Hastings). They mined zinc (New Jersey Zinc). They grew tobacco and rolled cigars (Consolidated Cigars). They made mattresses (Simmons) and they made caskets (Elgin Casket Division, Elgin, Illinois). All of these places have something in common. Hardly anyone who lives in the communities of these former industrial sites remembers that they were owned by Gulf and Western Industries. Why is this?

Then in 1966, Gulf and Western took over Paramount Pictures.

Gulf and Western’s Annual Report to Shareholders, 1970s

From the 1960s until the late eighties, while Gulf and Western was making bumpers here in Grand Rapids, they were also producing films like the Godfather, Rosemary’s Baby, Grease, Indiana Jones, Flashdance, Love Story, Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory and Star Trek. By the late sixties, the company founded right there at Ann and Alpine was 69th on the Fortune 500 list.

Why don’t we remember this company? And why don’t we remember its origins in Grand Rapids?

Time Magazine, 1969

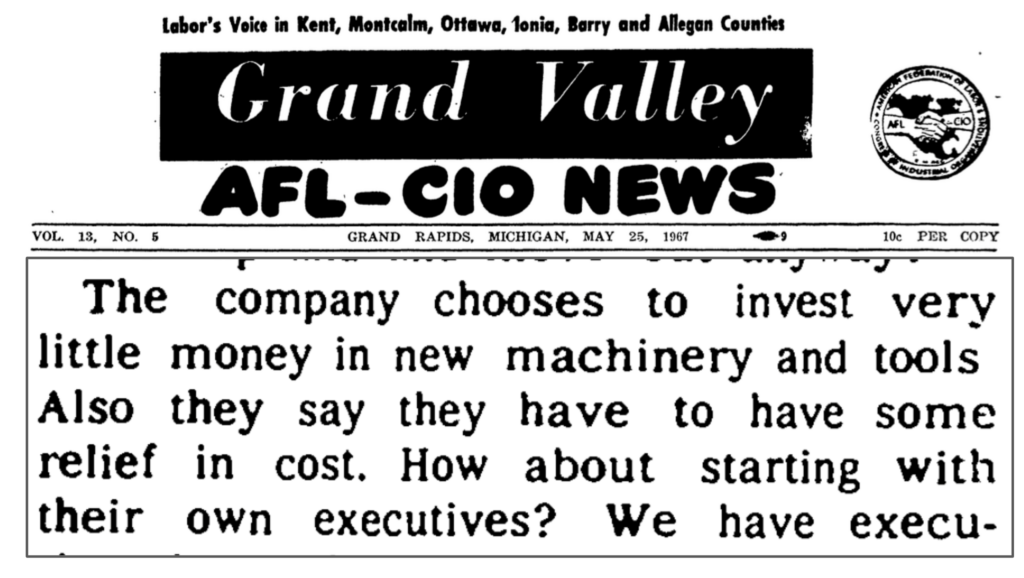

One might hope that a multi-industry company such as Gulf and Western would spread earnings across multiple industries to ensure that workers would not be subjected to wage freezes, layoffs and benefits cuts as other large companies sought cheap labor overseas. But for all of Hollywood’s shiny optimism, hope only gets you so far. In reality, when a factory was taken over by Gulf and Western, employees reported decreased safety, overly-complicated leadership structures, and waves of layoffs

Grand Valley AFL-CIO News and The Grand Rapids Press

Local labor news is awash with workers’ accounts of employment experiences at Gulf and Western. For example, an employee at their E.W. Bliss plant reported,

“Everything that has been worth something here in the past has been skimmed off by the company…even employees hope.” Another observed, “Executives at the Gulf and Western Automation and Appliance Division had a Christmas Party at Blythefield Country Club. After hearing the tales of woe about losing money, we wonder how they afford it.”

Ironically, in 1972, Gulf and Western Industries paid no federal tax dollars whatsoever.

To be sure, this was true for most multi-industry companies at the time. According to one worker at another multi-national conglomerate, “We got the mushroom treatment. Right after the acquisition we were kept in the dark. Then they covered us with manure. Then they cultivated us. After that they let us stew awhile. And finally they canned us.”

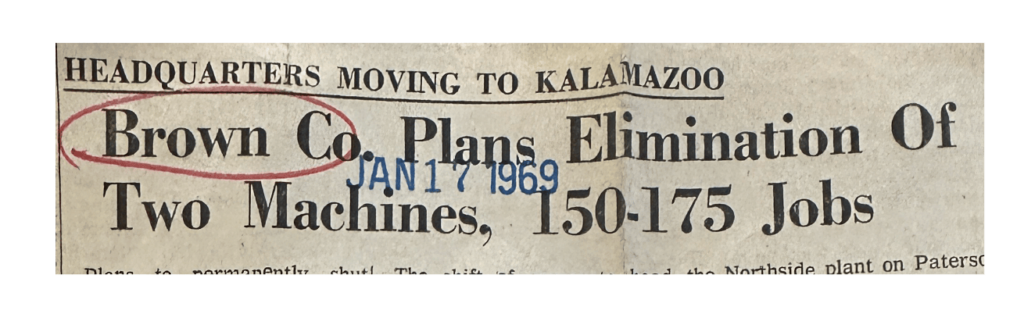

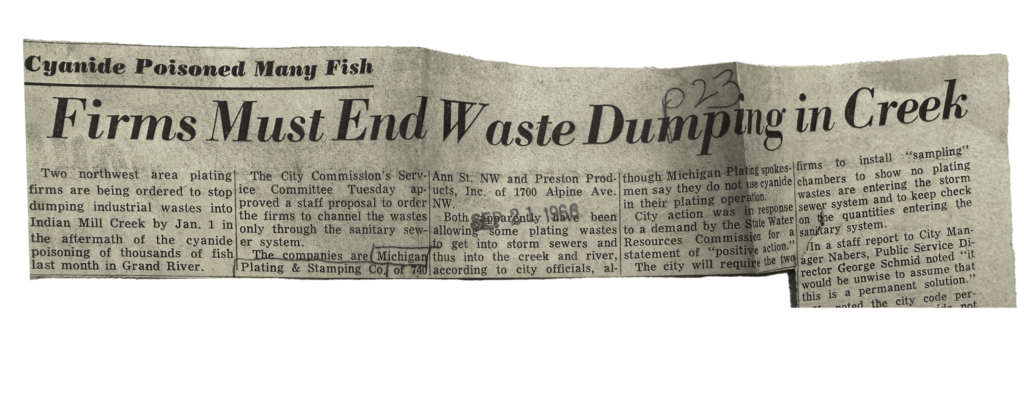

But it wasn’t just cutting employees’ wages and safety measures. For example, at Ann and Alpine, Gulf and Western was accused of allowing chromium, cyanide, and nickel to enter the Indian Mill Creek. The company also illegally dumped chromic acid at a nearby farm. Once, Gulf and Western emitted so many fine iron dust particles into the air that all the cars nearby broke out with boils of rust.

The Grand Rapids Press

As more countries were welcoming overseas companies to exploit their cheap labor, hard-fought federal environmental regulations were enacted in the US. That’s when Gulf and Western began closing factories. Then in 1983, the company’s president decided to sell the remainder of their factories, and use the money to invest in television stations and amusement parks. A man suffocates in a cave. Outside there is a carnival.

One worker at Ann and Alpine put it this way:

“Gulf and Western sold its firstborn…I guess if I had to choose between “Beverly Hills Cop” and us, I’d probably make the same choice.”

In 1989, Gulf and Western was renamed Paramount Communications. In 1994, Paramount merged with Viacom. In the late 1990s, the very first site of Gulf and Western at the intersection of Alpine and Ann was bought by a metals recycling firm. The new owners were required to clean up contamination and contain the left over chromium tanks in an underground concrete barrier. They did so primarily with funding from state taxpayers.

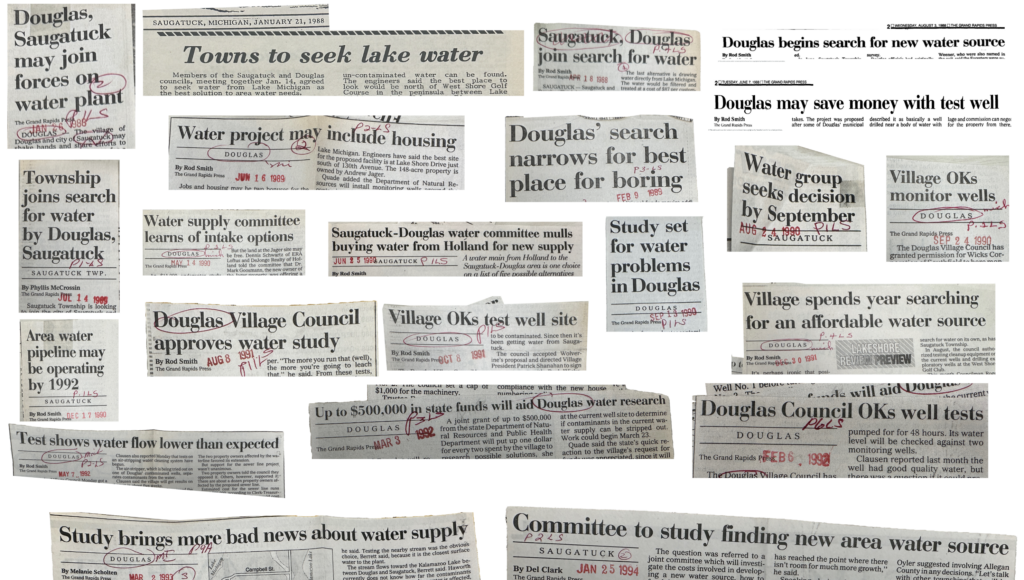

The new owners of the land at Alpine and Ann are not the only former Gulf and Western factory that had to address environmental impacts decades after Gulf and Western jumped ship. Fifteen years after a Gulf and Western factory in Douglas (Chase Manufacturing) closed, the city discovered that volatile organic compounds from Gulf and Western’s degreasing machines had infiltrated their main municipal drinking water wells. Douglas spent the next decade looking for a new water source, as the state and local governments funded survey after survey. Despite their location on the shores of Lake Michigan, Douglas was forced to implement water usage restrictions.

Years of reporting on Douglas’ ongoing attempts to locate a safe water supply, The Grand Rapids Press

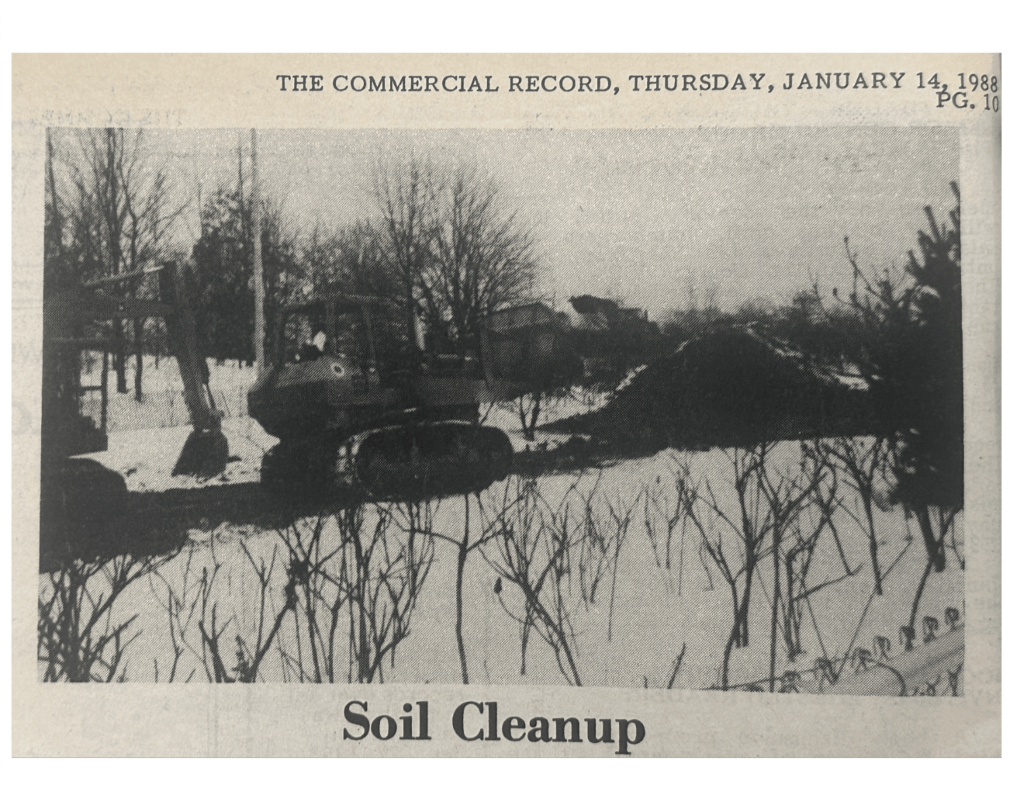

Then the state notified Douglas residents that the area directly behind the elementary school where children played was contaminated with chromium, lead, zinc and cadmium. It took the state nearly a year to locate funding to begin cleanup. Once cleanup started, it took nearly a decade to remove thousands of cubic yards of contamination from the area.

The Saugatuck-Douglas Commercial Record

The Saugatuck-Douglas Commercial Record

The Grand Rapids Press

All that is left of the former factory is the foundation. There is much contamination underneath, and the village and state lacks the funding to clean it up. So the foundation must stay in place.

Sections of the factory floor at the former Gulf and Western Chase Manufacturing site in Douglas, Michigan.

Gulf and Western’s track record is not unique. You’d be hard pressed to find a plant owned by a large corporation that did not lay off workers and leave behind contamination. It is important to question the motives of any large company that claims to bring jobs to a community. They may end up just making a mess.

Pollution has economic impacts as well.

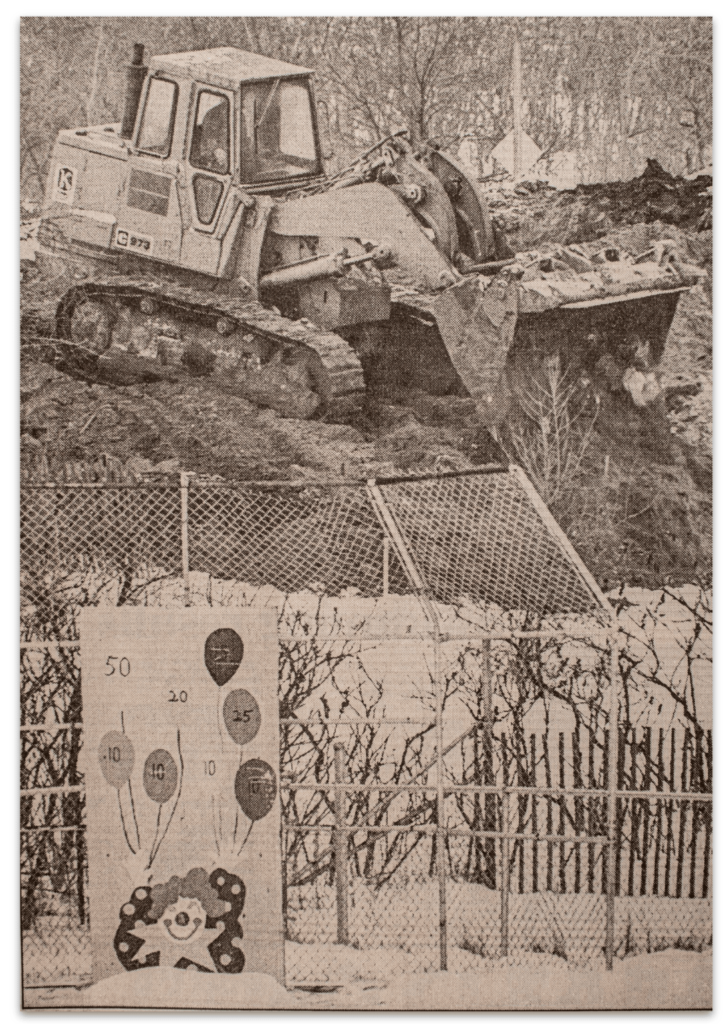

When Gulf and Western let go of their plastics plating plant on Oak Industrial Drive in Grand Rapids (FCM Plastics) in 1983, the company’s local management decided to purchase the plant in hopes of saving the factory’s 173 jobs. The new buyers secured a loan from the City of Grand Rapids.

By 1989, the factory on Oak Industrial employed only 20 people and it declared bankruptcy. The local management owed the city $746,000 for the loan and back taxes and nearly a million dollars more to Gulf and Western. The land was appraised and was found to be worth nothing–it was too contaminated from the years of Gulf and Western’s plating operations.

The Grand Rapids Press

As one article at the time noted,

“City commissioners, entrusted with taxpayer funds cannot take the same risks for which a private institution might be routine. City Hall is not a bank.”

The Grand Rapids Press

The loan money had come from a fund ordinarily reserved for “Community Development Block Grants.” These funds are given to cities across the country by the federal government for improving housing, supporting block clubs and funding non-profits who help the homeless.

The following year, the city was forced to cut $380,000 from this funding, skimping on much needed services as more jobs and tax dollars were drained from the city.

It didn’t end there. Desperate for a buyer, the city and the company had little choice to whom they sold the plant. Ultimately, MacDonalds Industrial Products (not the restaurant chain) took it over. The purchase agreement stipulated that MacDonalds would be released from worker pension liabilities and could fire all of the plant’s current employees. The following year, MacDonalds had so many safety violations that the state threatened to shut them down.

The risky practice of taxpayers subsidizing private companies is more prevalent than ever. In 2023, Grand Rapids approved $103 million in tax breaks to developers to build “Factory Yards,” a mixed-use complex of retail and apartment spaces at the former site of Luce Furniture Co. A soccer stadium and amphitheater received a combined $318 million. One might ask: who are these places for?

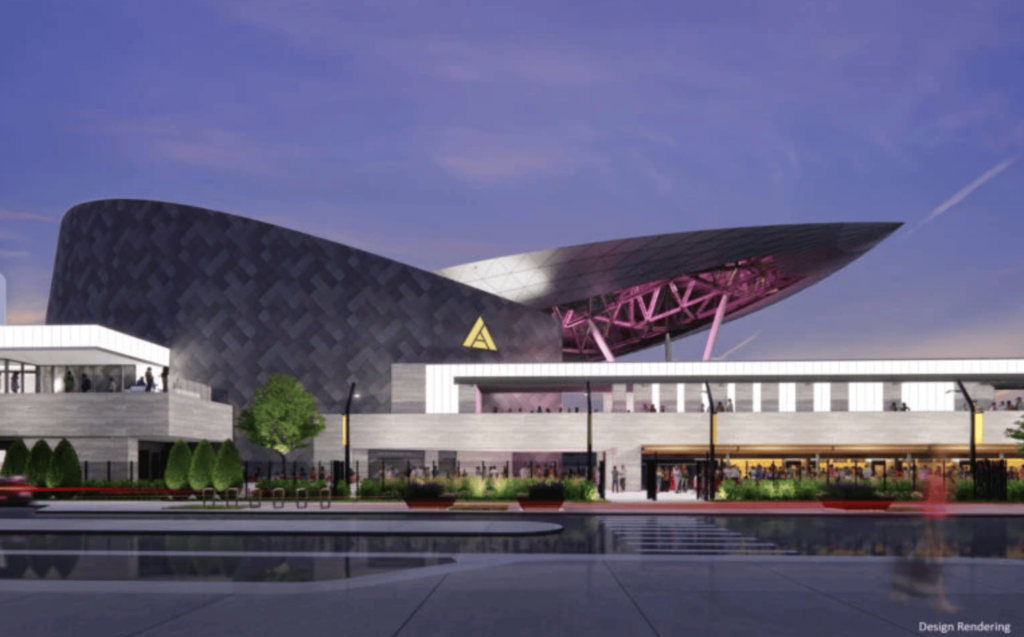

Rendering for a new amphitheater in Grand Rapids

Tax credits are often given to developers in exchange for a promise of jobs and other community benefits. But when companies promise these benefits, there is nothing legally binding that keeps them from reneging on these promises.

There’s a bigger irony here: many tax credits are given to companies to clean up decades worth of contamination at the sites they are developing. The tax credits are called “Brownfield Development Grants” and are given to offset cleanup costs. It’s important that these sites get cleaned up. But why should taxpayers be the ones who continue to pay?

Yet there’s some hope here. In some instances, the federal government and local communities alike have been able to obtain damages from Paramount Global, which is the company now liable for many of Gulf and Western’s former industrial sites. In fact, the city of Douglas is investigating ways to hold Paramount accountable to help pay for cleanup of the Chase Manufacturing site.

In fact, Gulf and Western’s successor company, Viacom, and their successor, Paramount Global, which inherited many of their liabilities, is responsible for up to 30 federal superfund sites across the country. They have yet to pay for all of their damages.

So I ask you: when you watched The Godfather or Grease, did you realize that the company that made it was founded in Grand Rapids? Did you consider that the your labor, your family’s labor, your neighbor’s labor, your environment subsidized these culture-shaping films? Are the real heroes Indiana Jones and Charlie Bucket? Or are they the workers and community who endured the cuts, slashes and shouldered the burden of environmental degradation? Who are the real protagonists? Are they Danny Zucko and Michael Corleone? Or are they us?

And I ask you again: Why don’t we remember this company, let alone the fact that it started right here, in Grand Rapids? Perhaps cultural amnesia is convenient for those in power.